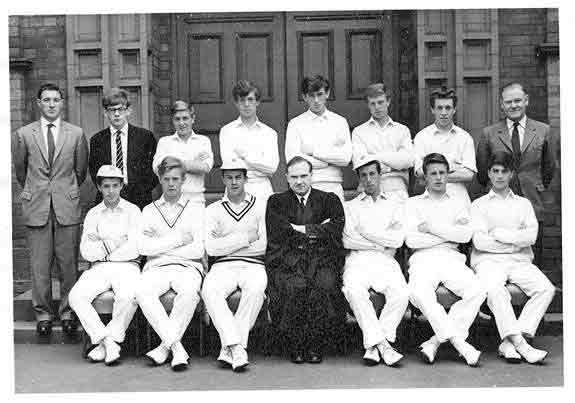

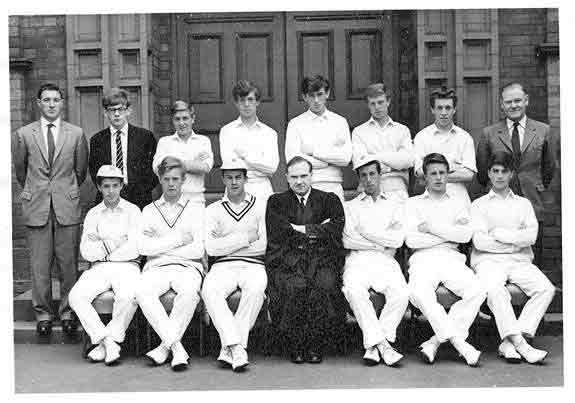

First XI Cricket Team 1964

Back Row: Mr Jones, Steve Brazier, Barry Cooper, Brian Bullock, Geoff Goodwin, Richard Law, Joe Dickson, Mr Thompson

Front Row: Roger Nash, Tim Smith, Jack Cartwright, Mr Douell, Tony Eves, John Bennett, David Gough

by Steve Brazier

Just before Easter in 1965, returning wet from another miserable games period at Dunstall Park, I entered the prefects' room and, vowing never to play rugby ever again, threw my tattered rugby shirt to the top of the full length sash windows. There it remained hanging ten feet above the floor until I left for college at the end of the year. The school magazine published my article- "Memoirs of a Short-Sighted Rugby Player. It was well received though I doubt if anyone appreciated the bitter irony with which I had written it.

While summer games periods offered respite from what I considered a very dangerous sport, they were just as barren. I would kill time with activities like the shot-putt, which required no effort and allowed ninety minutes of chatting with other non-combatants. Meanwhile the First and Second eleven played cricket on the field. I was not much good at cricket either but enjoyed playing it In the street with a tennis ball. At school, with proper equipment, I found the ball too hard when mishandled by the incompetent and the short-sighted. My sporting inadequacy was a concern at school where manly sporting prowess was rated above academic achievement and seemed the key to social success.

Looking for another source of sporting kudos, I asked about becoming the scorer for the school cricket team. This required statistical accuracy and a good knowledge of

the intricate rules and conventions of the game, which I thought I possessed. Tantrums among cricket players are more normal than you might expect and each game had

histrionics from bowlers whose appeals had been denied by umpires, batsmen run out by incompetent team mates and jealousy over the batting order. During a match,

umpires conduct a complex silent dialogue with the scorers around whom spectators and players crowd to enquire about scores, fall of wickets and other mundanities.

In short, the scorer is the focus of attention, the fount of knowledge and the centre of the mysteries and rituals of cricket. While lacking the coveted machismo so important

in the teenage pecking order, the scorer gets lots of attention and street-cred while avoiding the anxiety or injuries suffered by players.

First XI Cricket Team 1964

Back Row: Mr Jones, Steve Brazier, Barry Cooper, Brian Bullock, Geoff Goodwin, Richard Law, Joe Dickson, Mr Thompson

Front Row: Roger Nash, Tim Smith, Jack Cartwright, Mr Douell, Tony Eves, John Bennett, David Gough

In those days the only live football match shown on television was the FA Cup Final. Football was my passion so I accepted Mr Thompson's invitation to become the

Second XI scorer subject to the condition that once a season on Cup Final Saturday early in May I would not be available. Either he was short of candidates or very keen to

have me because he agreed.

Every Friday afternoon I reported to him in Room 8 to collect the team's score book. Every Monday morning before assembly I returned it and gave him a verbal match report. This was often summarised twenty-five minutes later in Mr Douel's assembly announcements. The score book related more than statistics. If it had rained, the page was ink-stained and crumpled. If it had been fine, it was covered in honeydew from the lime trees growing along the railings on Newhampton Road East adjacent to the scoreboard. The high spot of the afternoon was the tea for which the scorer did not pay - a monster tea-urn, salad cream, fish-paste sandwiches served by gingham-clad girls at long tables in the domestic science room.

After a year I was promoted to the First XI. Now the game was taken a lot more seriously by the players. While the Seconds had been invaluable training for a scorer, not least in reaching outlandish places like RAF Cosford and Shrewsbury Grammar School on public transport for away matches. This was long before our modern preoccupation with Health and Safety, litigious parents, paedophiles and the blame culture, so we were usually unaccompanied to away matches by members of staff. Such trips into the unknown were always fun, meeting to catch strange buses, often not green and cream. Sometimes by train. Travelling with the Seconds was particularly enjoyable as no-one took the match or, indeed, anything seriously. The capers were fairly harmless, like putting pennies on the line to be flattened by the trains.

The Firsts' away games were fun too but the match and result were more important. And the scorer's status correspondingly raised. I always worked out batting and bowling averages immediately - so that the players' enquiries during and after the match could be dealt with - how a pocket calculator would have helped. I was hampered by my poor eye-sight, which made umpires' signals and the outcome of each ball a challenge. Fortunately there was always co-operation with the opposition's scorer to ensure accurate identification of each other's players.

From time to time, I was called upon to play. This was usually because someone had failed to turn up. It happened quite often in the Seconds because the attitude to the game was so casual that our players often forgot what day it was as well as where we were suppose to be playing. At home matches there was usually someone else to act as substitute. No matter how poor they were at cricket, they usually got the nod before I did. I did not mind at all missing the tedium of fielding, terror of batting and above all, ignominy of being the only one wearing grey trousers. I am reminded of an incident ten years later when I began to play football in a Nottingham Sunday league side. One morning early in my career I was as usual the substitute. One of our players was injured and I began to take off my track-suit only to find that a spectator had a pair of boots with him and was invited to replace the injured player instead of me. It says a lot about my love of football that I was not disheartened. In fact I graduated to a regular place as left-back. By then I was club secretary, which probably helped.

But to return to 1965 and the time of post-war teenage liberation. In addition to the hint of independence brought by the music of Dylan and the Beatles, I was drawn by the excitement of hitch-hiking. This is another pleasure much-curtailed by today's risk-averse society. I was also permanently short of money. So after a First XI match at Bridgnorth, Roger Nash and I decided to pocket the bus-fare and hitch-hike home. Getting a lift proved difficult so we began to walk. I am not sure of the logic here as we would never have got the whole way on foot. Anyway, by the time we had climbed up the Hermitage out of the town, we estimated that the bus with the rest of the team would be overtaking us soon. Too proud to flag it down and too embarrassed to be seen, we hid behind a bush as it approached. Soon after we got a lift and got home in good time.

I often scored for the Staff XI too. This was valuable as it brought acceptance among the teachers and instructive because it gave glimpses of their personalities. I now know from years of playing in the office football side, that team-games give an insight into the murkier depths of people's characters. Violence, rule-bending and ruthlessness are assets on the sports field and easy to spot. Indecision and faint-heartedness are hard to hide. Such traits are usually concealed in the world of work but once identified in the sporting context can betray under-lying character. As Machiavelli probably wrote: forewarned is fore-armed. Mr Jones', the games master's comments in my report went from the faint praise of "Tries hard" (1962) to "Most willing and well-liked" (1965). As my sporting abilities had not altered, that must have something to do with scoring for the Staff cricket team.

One incident stands out : a batsman (possibly Mr Askew) was struck by the ball on his thigh above the pad and his trousers burst into flames. Clearly carrying a box of matches in his pocket during a game was not a good idea.

Miss Heyhoe played for the Staff, though I think she had left to work for the Express and Star by then. It was a joy to see the reaction of other teams and spectators. Not only to a woman cricketer but to a woman who was a very good player. It was fun to wait for the most telling moment to announce that she was the Captain of the England Women's team. She gave me my only cricketing claim-to-fame. During one of those golden periods after summer exams, when we were required to attend school with nothing to do but mess about, we had a scratch cricket match on the school field. I was fielding on the boundary with my back against the tennis court fence and Miss Heyhoe was batting (it could feasibly have been her successor, Miss Macateer but the story would be less impressive). She lofted a shot high in the air and in my direction. When it finally came down, I caught it and the England Captain's wicket fell - to my fielding! It did not go to my head and since leaving school I have only rarely played in a cricket match and have never again acted as scorer. But during televised Test matches, I sometimes feel that the umpire is signalling a leg-bye in my direction.

And rugby ? I was as good as my word. I have never again touched a rugby ball. Not that I often managed that in my seven long years at Dunstall Park.

Team photos (also posted elsewhere on this site)

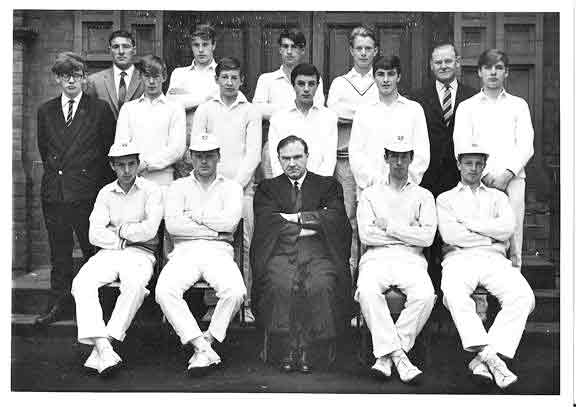

First XI Cricket Team 1965

Back row: Mr Jones, John Bennett, Michael Sharp, Tim Smith, Mr Thompson

Middle row: Steve Brazier, Roy Sedgewick, Eric Pullen, ? Parkes, David Gough, Phil Holmes,

Front Row: Roger Nash, Bill Tranter (Capt.), Mr Douel, Tony Eves, Dick Law

Roger Nash explains why some players have caps ...........

"Caps were awarded as school colours, which had to be earned. Bill Tranter and I got ours as fifth formers playing for the First XI. I scored 20 against Bridgnorth and was awarded colours and was the only one at that time to go out in assembly to collect the cap from Mr Douel. Tony Eves and Dicky Law got theirs later.

Photos Courtesy of Roger Nash and John Bennett

Published in the WMGS OPA Newsletter, Autumn 2014